“Finishing” captures all of the steps from the end of fermentation to the point at which the brewery ships the sake. Finishing includes adding water (“mizu wari”), pressing sake (“shibori”), filtering (“roka”), pasteurizing (“hi-ire”), bottling (“bin-zume”), and storage (“jukusei”). All of the decisions in these last steps—to do a step or not, and how—dramatically influence the sake.

There are three main methods of pressing sake with one being not to press it! It is also important to highlight that pressing is different from filtering. Although “nigori,” or cloudy sake is marketed as “unfiltered,” technically, nigori is lightly pressed or pressed and the sake lees, “sake kasu,” are mixed in again. Other than nigoris, after a sake is pressed, it is almost entirely clear and rid of particles.

A Yabuta is a modern, large scale press that removes almost all of the rice particles. Yabuta is the name of the company that makes the presses. Although Yabutas are thought of as a high volume, “mass” approach, sake makers even use them for their highest quality daiginjos.

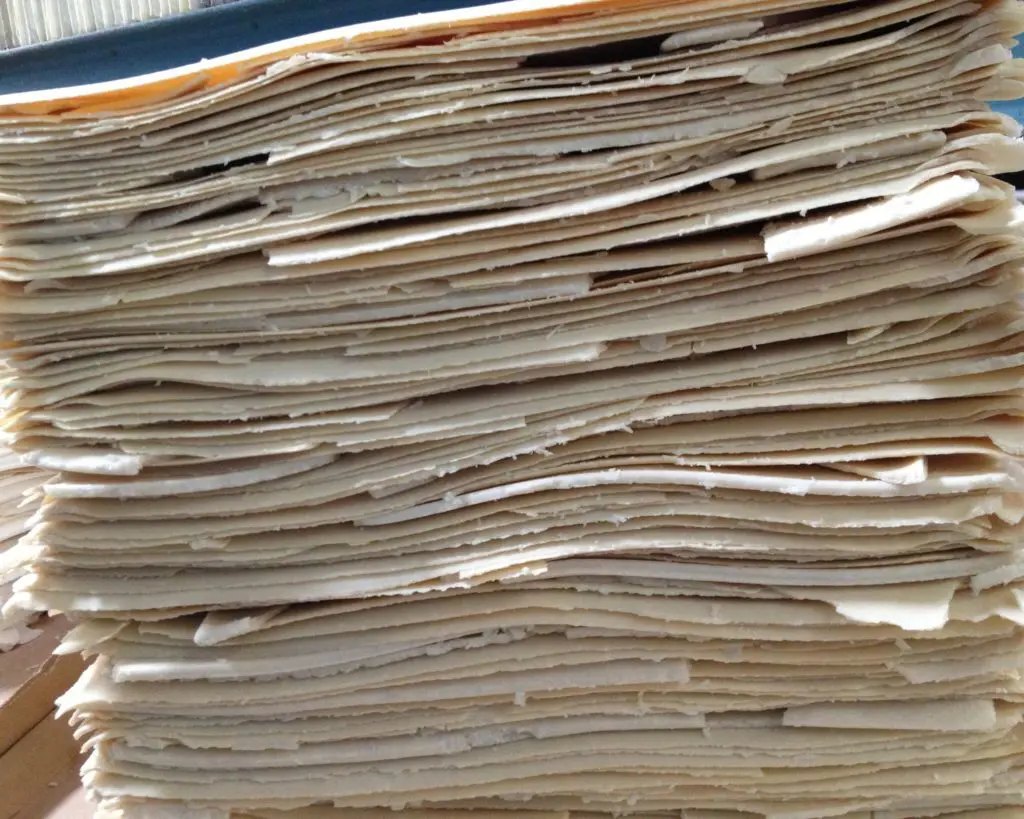

Funashibori is a traditional and refined method of pressing. Cloth bags are filled with the finished brew, folded up, and allowed to run free. More expensive “arabashiri” comes from the first run. After the juice has run free, the stacked bags are pressed from above. “Funa” comes from “fune,” meaning boat. Some breweries have their old, original wood funes, while others use modern, stainless steel versions. The clear sake is racked off into large bottles or smaller tanks. Funashibori sake has a soft, silky mouthfeel and a gentle character.

“Shizuku” literally means “drops,” so shizuku is the “drip method.” A nickname for shizuku is “kubi shibori,” with “kubi” meaning “neck.” Cloth bags are filled with the moromi, tied at the neck, and hung on bamboo poles at the top of a tank. The liquid runs down through the bag and the sake kasu at the bottom becomes a thicker “filter” of the liquid. The dripping sake goes from white and cloudy to somewhat clean. It is allowed to rest in the tank so the remaining sake kasu fall to the bottom of the tank.

It is then racked off in 18-liter bottles called “to-bin.” A “to” is a measurement of sake, 18 liters, and “bin” is a bottle. While most sake makers market their shizuku as shizuku, occasionally, a sake maker will label the sake “to-bin dori,” to capitalize on the small portions that are created.

The shizuku method is labor intensive, time consuming, and small scale. Sake makers use this method for their most expensive sakes, especially competition-grade daiginjos. The toji, brewmaster, will sample the different “to-bin” to identify the best and then submit those bottles to national and regional competitions.

After these first two steps of finishing—pressing and filtering—the sake might be immediately released. “Shiboritate” (shibori tah-tey) is sake that was just pressed. Shiboritate can also be filtered. Either way, it is released fresh. Many people know “namazake,” unpasteurized sake. While most namazake is released in the spring right after pressing, the term “namazake,” technically refers to the lack of pasteurization. Shiboritate refers to it being freshly pressed. Thus, “shiboritate namazake” is a standard but exciting labeling term.

Filtration, “roka,” comes after pressing with the goal of removing more rice particles and stabilizing the sake. Charcoal filtration is used for the majority of sake simply because it is the method of choice of large breweries. They use it because it is the most precise, efficient, and reliable. There are regional associations with this method because so many large producers are in Hyogo and Kyoto prefectures. However, Niigata is a prefecture of smaller breweries and the method is integral to the Niigata style known as “tanrei karakuchi,” or light and dry. Charcoal filtration is also widely used by small breweries. Thus, it is not accurate to associate it with low quality. Other than charcoal filtration, breweries use paper, fiber, or centrifugal force filters.

After sake is pressed, it is pasteurized, or not, in a number of ways. Pasteurization is “hi-ire” (he-eeray”).

Most sake is pasteurized twice, first, in the coil that runs from the resting tank to the bottling line and, second, in the bottle as it comes off of the bottling line in a “shower” that sprays hot and then cold water. There is no special labeling or indication for sake that is pasteurized this way.

Some sake is only pasteurized once, in one of the ways described above or by submerging bottled sake in crates in large vats that are filled with hot water and then circulated with cold water. Pasteurizing sake in the bottle is the most gentle method because it is most gradual and indirect.

There are also variations in the order of pasteurizing once. “Namachozo” is the method of bottling unpasteurized sake, “namazake,” and then pasteurizing once in the bottle before shipping. “Namazume” is the method of bottling unpasteurized sake, pasteurizing it in the bottle, storing, and shipping out months later without pasteurizing again.

“Hiyaoroshi” is fall, seasonal sake, which is made in the namazume way—bottling, pasteurizing, storing, and shipping in September without another pasteurization.

Completely unpasteurized sake is “namazake.” As has been mentioned, most namazake is released in the spring, having just been pressed. Namazake is thought of as a spring, seasonal release, but it can be sold year-round and there must be breweries that do this.

How sake is stored is extremely important. Sake can be stored in the bottle or in the tank, before or after pasteurization, which can be done in a few different ways. Then there is the storage temperature and the duration and release.

We avoid using the term “ageing” because it is used in wine in a different way. There is “aged sake,” “koshu.” Koshu is a specialty type that is made in limited quantity. Many sake makers don’t even make it. Koshu will, generally, be released three years or more after it is made. It might be stored in the bottle or tank, even a cedar tank.

“Jukusei” is the term for “maturing” sake for a few months or a few years, at very low temperatures, in the bottle. We have some sake makers who “mature” sake for two years or more at -5 degrees celsius, 23 degrees fahrenheit. Sake makers generally stay below 5 degrees celsius, 41 degrees fahrenheit, for any “jukusei,” matured, sake. Some sake makers are maturing sake in some kind of ice or snow and marketing some selling point here.

Separate from any specific technique or selling point, most sake is made during the winter and released starting in the fall. However, if sake makers run out before their matured sake is ready, they might have to release “shinshu,” new sake. The sake might still be pasteurized and even filtered, but it will be “young.” Shinshu is not a labeling term: it merely captures the phenomenon of releasing early.

A major trend in the sake world has been towards “muroka namazake genshu”—unfiltered, unpasteurized, and undiluted sake. This is sake in its most natural form and natural wine lovers often gravitate to it.

It is said that there are ten thousand ways that one sake is different from another. We hope you understand this now. We also hope this acts as a guide as you buy sake, taste it, learn, explore some more, and enjoy, hopefully, much more than before.