In the waning of the Tokugawa Period (1603-1867) and the start of the Meiji Restoration (1868-1889), the newly formed federal government took steps to reduce the power of local samurai. Laws were passed to prohibit farmers from making sake and sake makers from owning land and growing rice. Having to make a decision, many sake breweries incorporated during these years, from our portfolio—Marumoto, Nakao, Tajima, and Hakuto Breweries, and Huchu Homare.

As the sake industry has grown and increased in quality, the relationship between sake makers and rice farmers has grown tighter. Most craft breweries contract with local farmers to grow rice for them, “keiyaku saibai.” Sake makers commit to volumes, varietals, and price targets, and farmers aim for quality levels and yields. Breweries, especially larger ones, also rely on raw rice wholesalers or “processors” (rice polishing and warehousing companies) for larger volume, lower quality products.

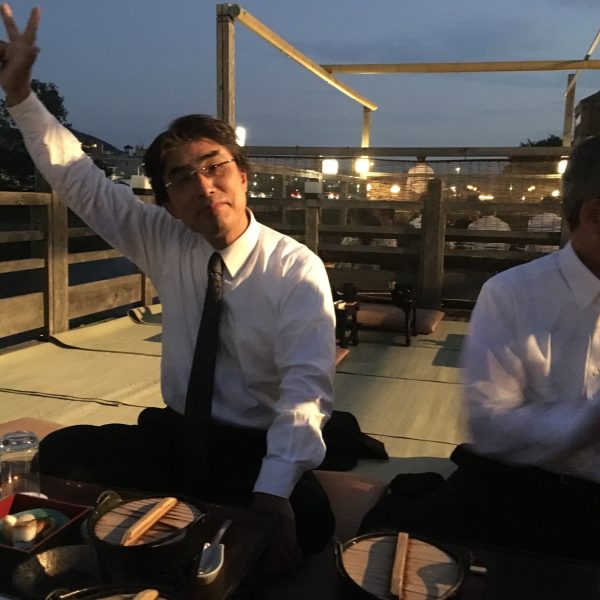

In the early 1990s, seeing the evolution of rice cultivation as a part of sake making, Marumoto-san decided that he wanted to grow rice, himself. He felt that sake makers should own and manage the process and product, from the source to the bottle. He started growing rice on the limited, legal amount of land that he could. Over time, he started leasing land from neighbors. He also started hiring farmers as sake makers and retaining his sake makers year-round to grow rice with him.

The rice he chose to cultivate was Yamada Nishiki. The brand he launched was Chikurin, named after the mountains behind his brewery. Some thirty years later, Chikurin is still one of the only sake brands that is 100% “estate-bottled,” made from homegrown rice. The fact that it is Yamada Nishiki doesn’t hurt, either.

This story and commitment has earned the Marumoto Brewery the nickname, the “Farmers’ Brewery.”